Core Scientific (CORZ) Opportunity Analysis: The High Density Technology

CoreWeave tried to acquire this company, why?

Please before diving in, read this disclaimer.

🤝 This edition was offered to you by the Paid Subscribers of Hidden Market Gems, if you want to get the access to all the future article as they do, you should subscribe!

For Christmas, I offer you a special offer! To say a big thank you for this year and show you my gratitude. If you hesitated until now, you should know that the quality of the content will seriously go deeper.

Things will get really interesting and surely paid subscribers will get everything. Claim your slice of the cake now!

Over the past few years, I’ve been watching banks, critical institutions, and the systems behind them, and I keep coming back to the same slightly uncomfortable conclusion: the vault has changed address.

It left stone, counters, reassuring facades. It moved into anonymous buildings filled with racks, alarms, redundancy, cables, and heat. A modern “account” is no longer a human relationship with an institution. It’s a permission system. Keys, logs, access rules, audits, alerts. And once the vault becomes a system, questions about stored value, ownership, and settlement inevitably follow.

The world is already dematerialized in practice. Capital moves as signals. Payment flows are messages. Ownership becomes access rights, contracts, proofs.

Even when we think we’re buying something tangible, we’re often buying a line in a registry, and that registry lives on digital infrastructure. We still tell ourselves the story of the “real,” but the plumbing has moved. It smells like warm metal and cold coffee, not the dust of a Swiss safe.

The real thesis is not “Bitcoin will replace every collaterals.” Bitcoin can be a consequence, an asset, a variable. The core movement is broader and much harder to reverse: value is migrating into digital registries, and those registries require a generic, industrial vault layer that every sector can rent.

That’s where the data center stops being “IT” and starts behaving like an institution. A vault you lease. Expand. Standardize. What high-density colocation (HDC) actually sells is exactly that: you’re leasing a vault capacity. Power, cooling, access control, redundancy, connectivity, 24/7 operations. You deposit racks instead of depositing gold. Same logic, different form.

By the way, alongside with TSCS we made this piece that basically makes you the smart pants on datacenter, which today is true edge.

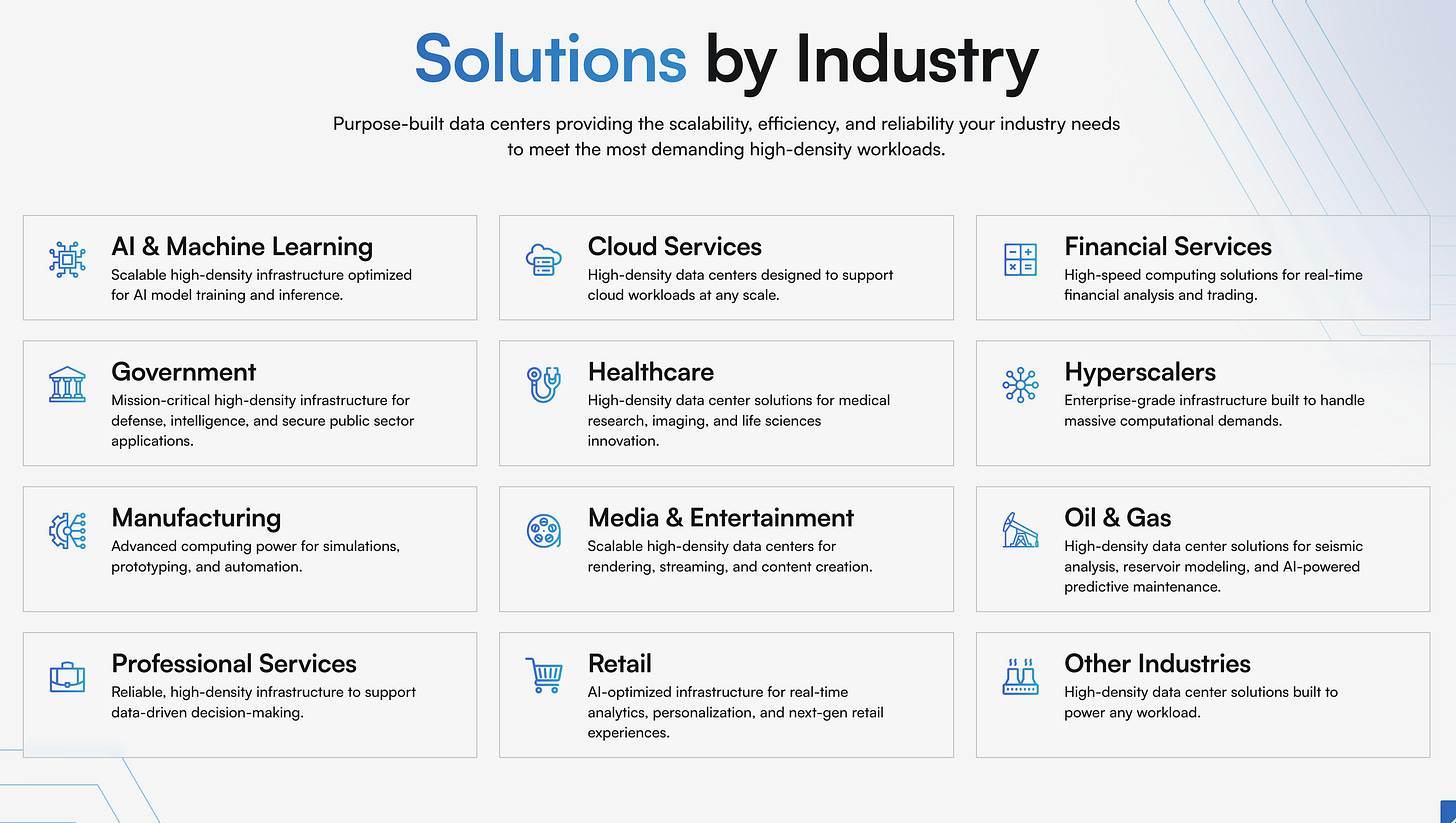

This shift touches everyone because every industry is converging toward the same primitives. A hospital, a trading desk, an e-commerce platform, a manufacturer, a ministry. They all end up depending on three things. (1) A registry (data, transactions, records, titles, identities). (2) Proof and access control (who can read, write, sign, move). (3) Continuity (if it goes down, value stops). The result is structural: the modern vault no longer belongs to a single sector. It becomes a shared layer. You pay for an SLA, for density, for uptime, for governance. Everything else is sector packaging.

At that point, blockchains and distributed ledgers play a precise but meaningful role: they shift part of trust away from institutions and toward verifiable systems. In certain contexts, they make it possible to audit, prove, and verify state without asking permission. They don’t replace security as a whole. They don’t protect endpoints, human error, coercion, or politics. But they rewire the base: the integrity of a registry can become a technical product. Once the base changes, the boundaries between “finance,” “payments,” “data,” and “identity” get softer, and new rails appear.

The reality check, the thing that keeps this from turning into sci-fi, is that the immaterial never exists alone. The network rests on the physical: energy, land, chips, subsea cables, jurisdictions, operators. The vault has become digital, yes. But it is still plugged into the physical world, which means it’s plugged into politics. The central question becomes blunt: who controls the data centers, who controls interconnection, who controls the keys, who controls the energy. And who can cut who off.

That’s why I see a layered future rather than a monolith. At the top, institutional rails will keep dominating the official economy, because states never fully surrender the core of the system. In the middle, digital transaction rails keep gaining ground because they match usage (stablecoins, faster settlement, programmable money movement). At the bottom sits the vault-infrastructure, the layer that makes everything else possible: data centers, high-density colocation, interconnection, cybersecurity, key management. The migration will happen because efficiency pushes in that direction. It will remain contested because sovereignty will try to keep control.

What we’re watching now is not a trend but an architectural shift. Critical/Sensible businesses are turning into infrastructure companies. Registries are turning into battlefields. And stored value, in the broad sense, is starting to look like what the world already became: a network: a combination of rules, keys, energy, uptime, and operated trust.

And you have been following me on this until now, I have to present you a concept that completely makes sens now: HDC = High-Density Colocation.

In a nutshell,

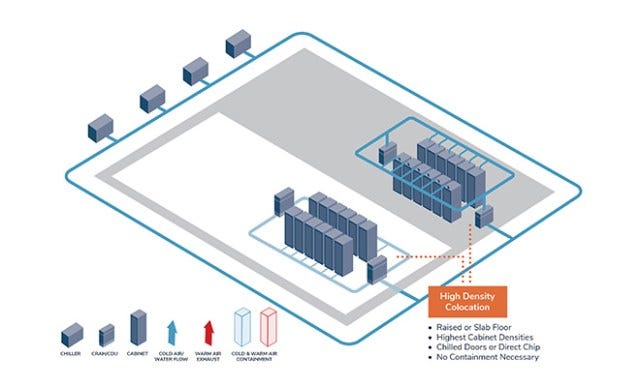

High-Density Colocation means you rent data center space that can handle a lot of power per rack (high kW density), plus the supporting infrastructure: cooling, redundancy, physical security, 24/7 operations, and connectivity. You bring the servers (often GPU-heavy). The operator provides the “vault”: power, heat removal, uptime, and controlled access. Electricity is often billed as a pass-through, while the operator earns margin on fixed colocation/license fees and operational services.

Why HDC is the right solution for critical infrastructure

Critical infrastructure has one obsession: failure is not an option. HDC fits because it turns the messy, expensive parts of reliability into a specialized industrial service.

I have been looking for a company that will be well positioned for this subject, and like last time, I will ask myself several questions to :

understand the business ✔︎

guess how they can tackle the issue ✔︎

are they the best positioned? ✔︎

are we in or next quarter? ✔︎

I came across several companies, but one really caught my attention.

Sometimes you have a feeling about a company. So you go in.

Don’t underestimate the human instinct, it is actually really powerfull.

Here’s the company:

CORZW 0.00%↑ Core Scientific

Core Scientific runs data centers and rents out very high-power, high-cooling space (racks/cabinets/cages) to customers who want to deploy heavy workloads (usually GPU clusters for AI/HPC, sometimes other compute-intensive stuff).

Core Scientific caught my attention because CoreWeave tried to acquire them. Why? Because this former Bitcoin mining company is moving to critical infras for AI. Yes, they are going to another use case because it uses the same expertise as what they formerly did (still does for now). That is for me the signal, because high density… man lots of folks do it: Digital Realty, Equinix.. so what makes it special is the face of the chart, the volatile situation and the market talking about it as a BTC miner, for me, there is an asymmetry.

What Core Scientific provides

Core Scientific runs large, purpose-built power sites (think: industrial-scale “vaults” for machines). They monetize those sites in three ways: they either use the power themselves to mine bitcoin, host someone else’s mining machines, or rent high-density data center capacity (HDC) to customers running AI/HPC workloads. So in a list:

Lots of power per rack (high kW density)1

Cooling designed for that density (often with liquid-cooling capability depending on the build)

Physical security + access control

24/7 operations (remote hands, monitoring, maintenance)

Network connectivity

How they make money on it

Two main components:

A fixed “license/colocation fee” (this is where the margin is).

Electricity pass-through (the customer reimburses power costs; often little or no markup).

So HDC is basically “the vault as a service”: instead of storing gold, you’re storing racks, and paying for uptime, power, cooling, and security.

Here’s Core Scientific in plain English.

What they sell, and to who

1. Digital Asset Self-Mining

What they sell: bitcoin they produce themselves.

Who pays: the market (they sell the bitcoin they mine).

How it works: they own the mining machines, plug them into their power sites, mine BTC, then hold or sell.

(That line still drives most of today’s revenue.)

2. Digital Asset Hosted Mining

What they sell: “mining hotel” service.

Who pays: third-party miners who own the machines.

How it works: customers bring miners; Core provides power, space, cooling, ops; Core charges hosting fees.

Management explicitly frames this as shrinking because they are shifting capacity toward colocation/HDC. That’s what we want but I will talk about it a bit later in this piece

High-Density Colocation (HDC, formerly “HPC hosting”)

What they sell: high-power data center space that can handle very dense racks (often GPU clusters).

Who pays: AI/HPC infrastructure players, enterprises, hyperscaler-adjacent customers.

How it works: customers place their racks; Core provides power + cooling + physical security + 24/7 ops + network.

Inside HDC revenue, they split it clearly:

License fees / licensing revenue (this is the “real” service revenue),

power fees passed through to the customer (electricity reimbursement).

How they make money

Think “monetize megawatts”:

Self-mining: profit depends on BTC price, network difficulty/hashrate, and their power costs.

Hosted mining: margin depends on utilization + contract pricing, with lower upside than owning the miners.

HDC: margin depends on the license fee and on execution (delivering capacity on time, keeping uptime). The power pass-through inflates revenue but behaves more like a pass-through line item.

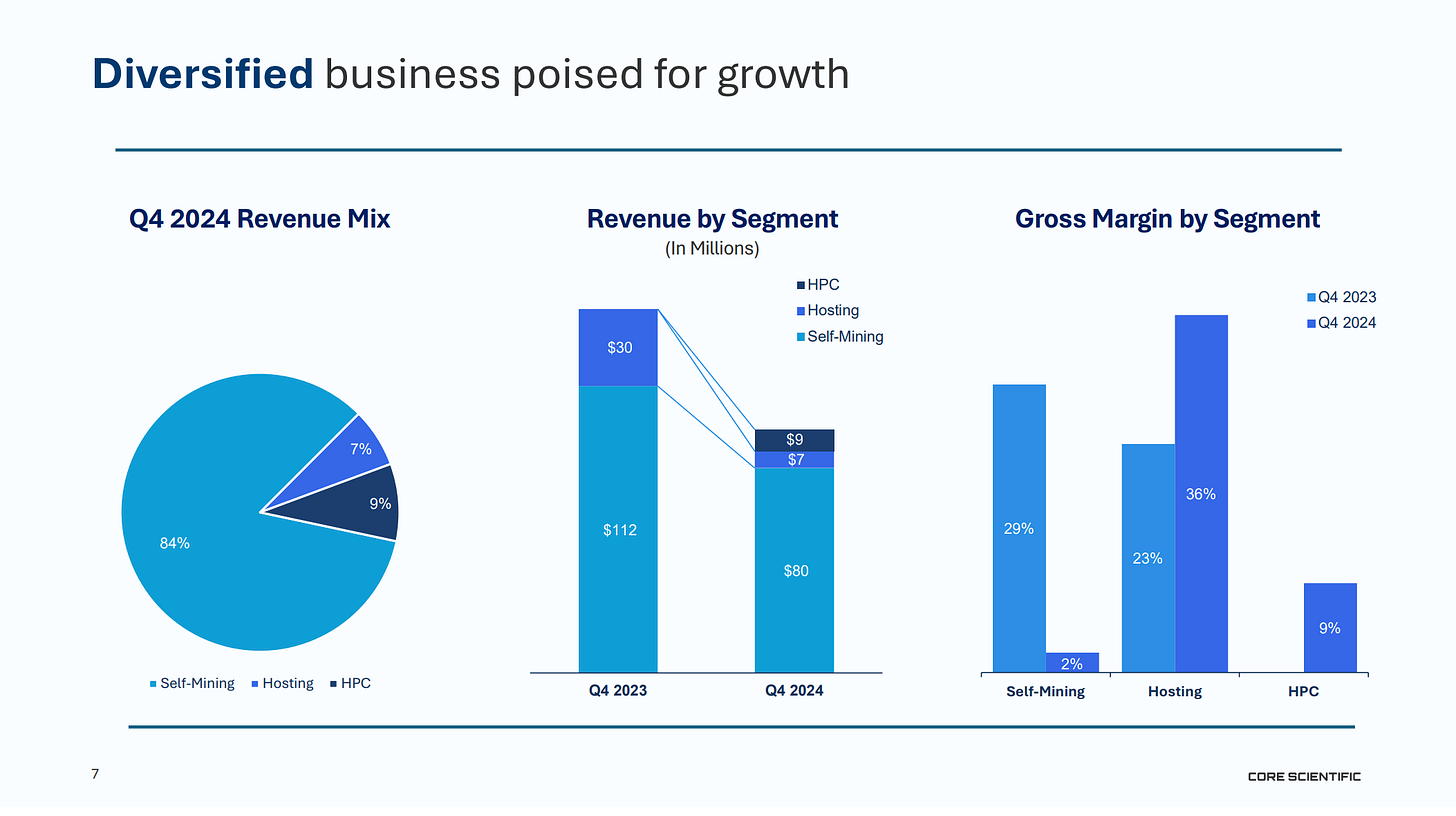

Revenue mix by segment (latest quarter in your files)

Fiscal Q3 2025 (three months ended Sept 30, 2025): total revenue = $81.1m.

Self-mining: $57.4m (~70.8%) (!) — that’s the part you want to see reduced over quarter.

Hosted mining: $8.7m (~10.7%)

HDC / Colocation: $15.0m (~18.4%) — our interesting part:

and within that $15.0m colocation revenue in Q3 2025:

License fees: $9.8m (the core revenue i.e. real value).

Power pass-through: $3.6m (electricity charged to the customer).

(plus maintenance/other)

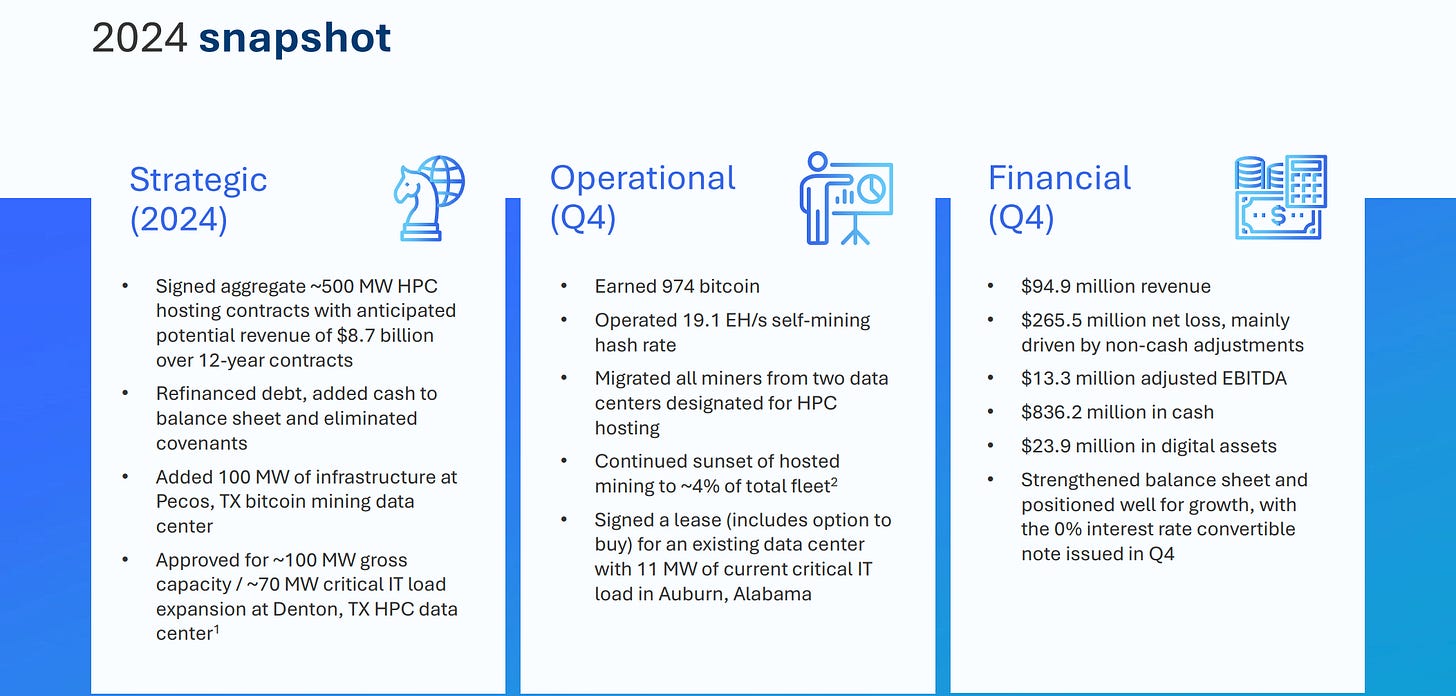

The U-turn that changes everything

Core Scientific’s U-turn is basically this: they’re trying to stop being valued like a cyclical Bitcoin miner and start being valued like a contracted digital-infrastructure landlord. The asset they’re betting on is not BTC. It’s power + sites + ops.

Why the pivot happened

Mining is volatile by design

Self-mining revenue depends on BTC price, network difficulty, and the halving cycle. You can run a world-class operation and still get your economics crushed by things you don’t control. Their Q2/Q3 2025 releases show exactly that kind of swing: BTC mined down hard year-on-year, partially offset by higher BTC prices. This is not sustainable.

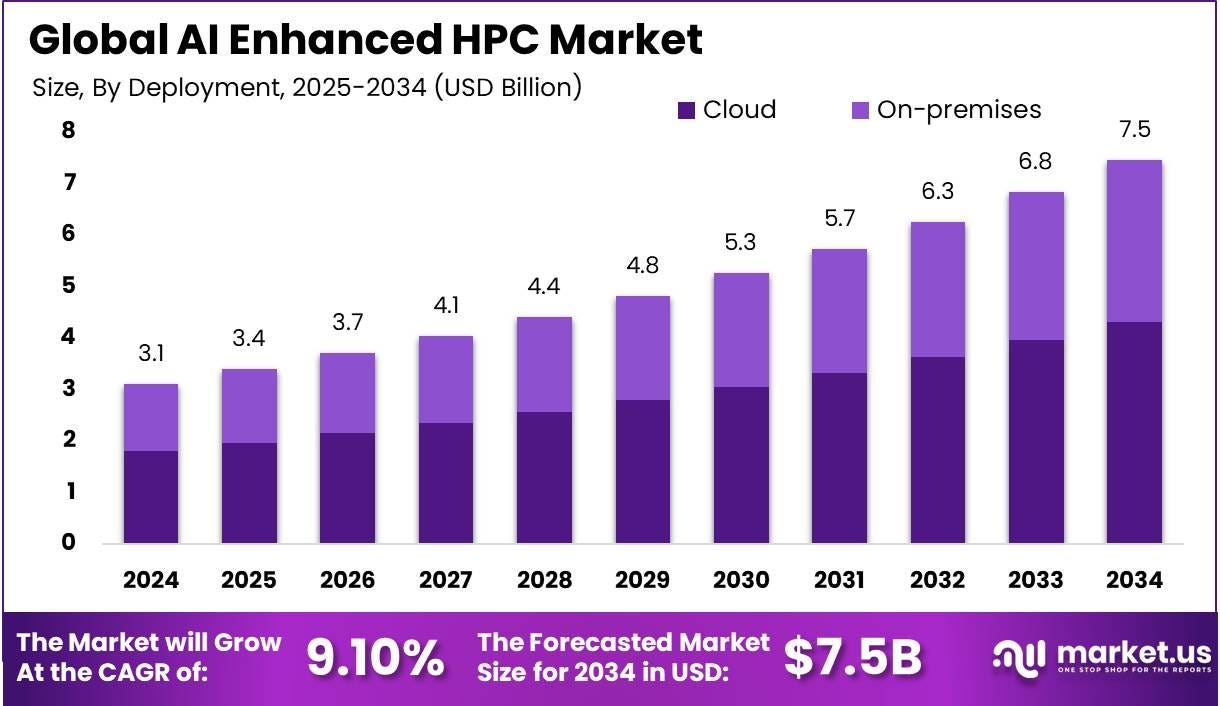

AI/HPC demand created a “new buyer” for the same scarce resource

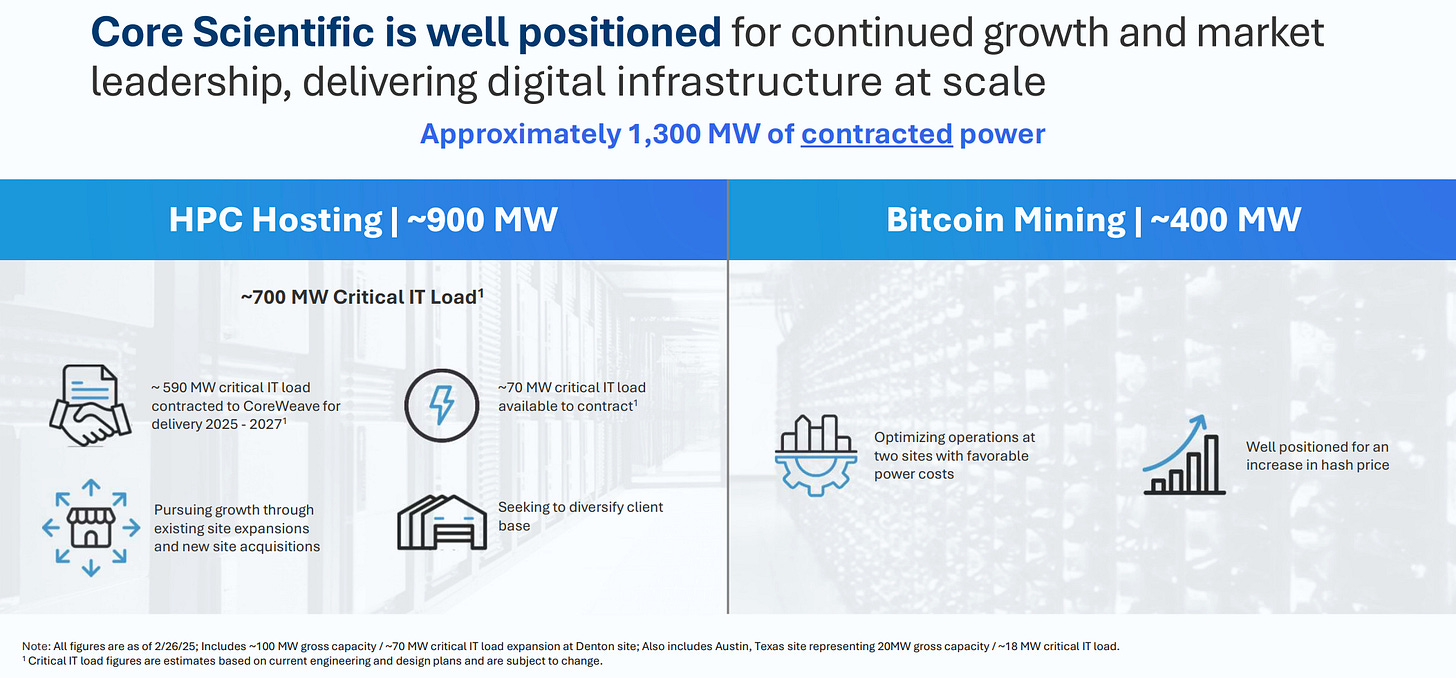

Their scarce resource is available, contracted power and facilities. So instead of using that power to mine BTC, they can lease it to AI/HPC customers as high-density colocation (HDC). They explicitly position themselves as a leader in “digital infrastructure for high-density colocation services,” and say they’re converting most existing facilities to support AI-related workloads and next-gen colocation.

What changed operationally (the real “turn”)

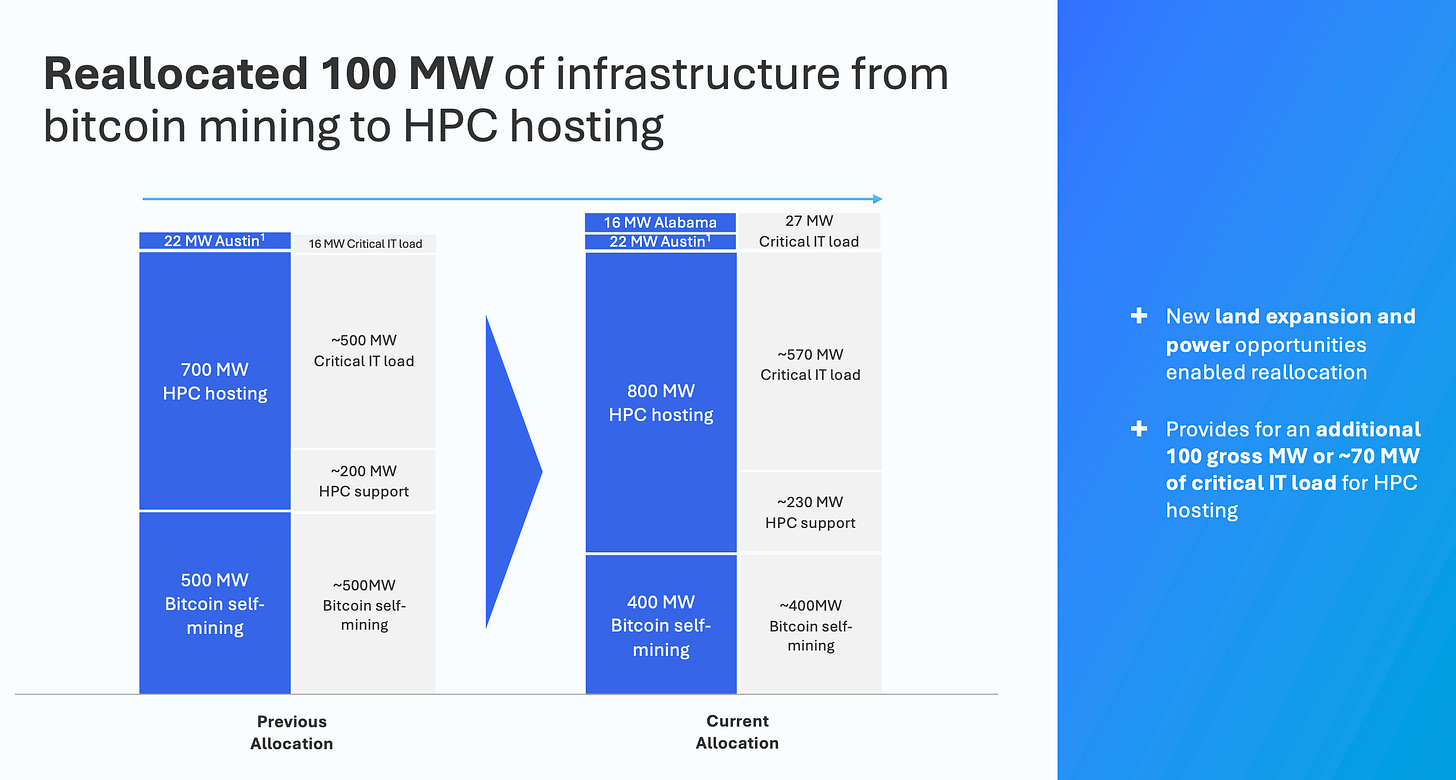

They didn’t just add a new segment otherwise it wouldn’t be that important. They started completely reallocating capacity away from mining.

In the Q3 2024 deck, they show they reallocated 100 MW of infrastructure from bitcoin mining to HPC hosting (HDC’s earlier label).

They also say they migrated all miners from two data centers designated for HPC hosting and continued the “sunset” of hosted mining.

By Q4 2024, they say hosted mining had been reduced to ~4% of total fleet.

That’s a genuine pivot: physically moving machines out, repurposing buildings, and turning mining footprint into data-center footprint.

The economic model they want instead

Mining = commodity-like cashflows

You “produce” BTC. Your margin breathes with the cycle.

HDC = contracted cashflows (closer to infrastructure)

You rent out high-density data-center capacity. Customers pay:

a license / colocation fee (this is the value-add revenue),

plus power fees passed-through to reimburse electricity.

So the revenue line can look big because it includes power pass-through, but the real margin engine is the license fee + utilization + uptime + contract terms.

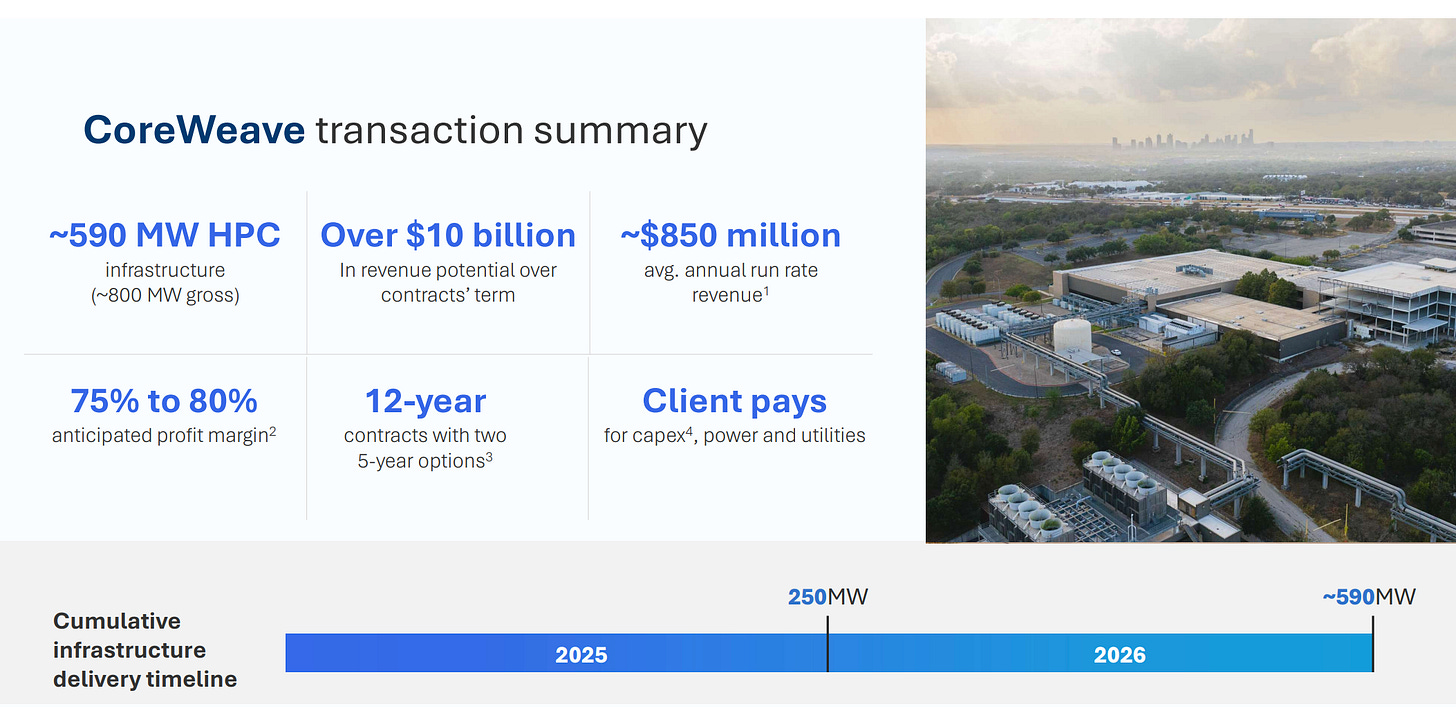

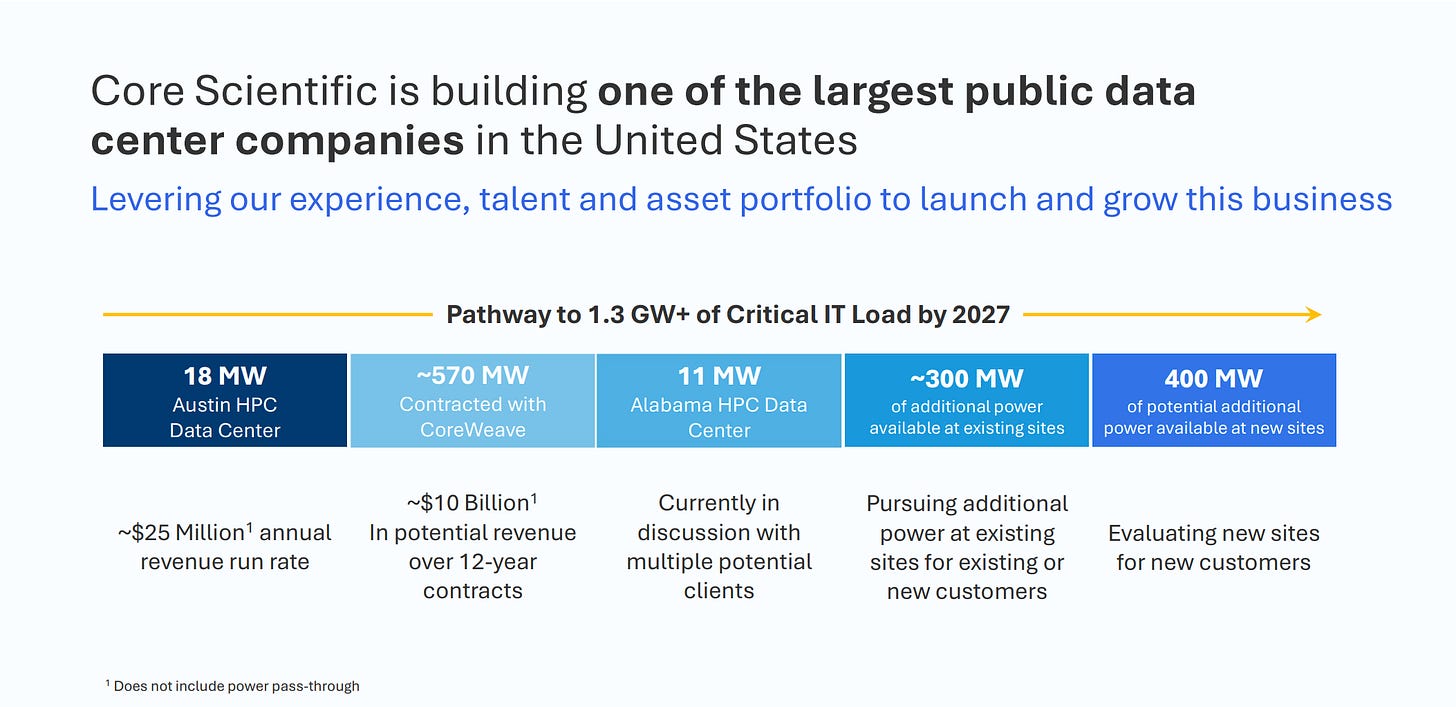

The CoreWeave deal is the pivot in one contract

Their decks spell out the logic: long-duration contracts, a defined delivery ramp, and a massive amount of capacity effectively pre-sold.

Q3 2024 deck: ~500 MW contracted with potential revenue of $8.7B over 12-year contracts, with a delivery timeline ramping from 200 MW to 500 MW across 2025–2026.

Q4 2024 deck reframes it at ~590 MW HPC infrastructure and “over $10B” revenue potential over contract term, with “client pays for capex, power and utilities” highlighted.

The strategic point is simple: they’re trying to lock in multi-year infrastructure economics, and even have a customer funding a big part of the buildout. That’s the opposite of mining.

You can already see the pivot in the reported numbers

They explicitly attribute segment moves to the strategy:

Q3 2025: hosted mining revenue down, “driven by the continued strategic shift to our high-density colocation business.” HDC revenue up (15.0m vs 10.3m).

Q2 2025: same story, hosted mining down because of the shift, colocation up due to expanding colocation operations (Denton).

What the U-turn really means in one line

Core Scientific is trying to turn megawatts into leases instead of turning megawatts into bitcoin and this will represent another growth engine. That’s my thesis

If we want to judge whether the pivot is working, one must ignore the branding and track three proof points:

MW contracted vs MW delivered (ready-for-service)

License fee growth (not just power pass-through revenue)

Customer concentration risk (how dependent they are on CoreWeave)

Guess what this is exactly what the next part is about:

MW contracted (the “backlog in power”)

Core Scientific’s own materials frame the HDC ramp as: ~250 MW by end of 2025 and ~590 MW by early 2027 (that’s the contracted trajectory they communicate).

That’s our denominator.

MW delivered / ready-for-service (the “reality check”)

And that is the frustrating part when I analyzed the business: in the Q3 2025 10-Q, Core does a lot of financial disclosure on colocation revenue, but it does not give a clean “MW ready-for-service as of quarter-end” KPI in the sections. So I can’t truthfully find for us a single “MW delivered as of Sep 30, 2025” number from the 10-Q.

So how do we do? We will estimate the MW delivered from… license fees!

That is the cleanest approach to back into “MW that are actually live and billing” using the contract economics.

In their deck, they give a rough magnitude: “Over $10B” over ~12 years for ~590 MW of infrastructure, and they explicitly present this as excluding power pass-through (so it’s essentially the hosting/licensing economics).

So the implied average hosting/licensing revenue per MW is:

$10,000M / (12 × 590) ≈ $1.41M per MW per year (ballpark)

Then you take what they actually reported in the Colocation / HDC segment:

Q3 2025: Licensing revenue = $11.398M (license fees + maintenance/other).

Annualized: $11.398M × 4 = $45.6M/year.

Implied “ready-for-service MW” (MW that are live and billing):

$45.6M / $1.41M ≈ ~32 MW (Q3 2025)

Same exercise for Q2 2025:

Q2 2025: Licensing revenue $7.096M, annualized $28.4M/year, so:

$28.4M / $1.41M ≈ ~20 MW implied

Simple read: using these rough economics, their HDC capacity that is actually billing may have moved from roughly ~20 MW to ~32 MW between Q2 and Q3 2025. The exact number will vary with pricing tiers, ramp schedules, and contract structure, but the direction and scale are informative.

Okay are still following me?

License fee growth vs power pass-through (your key point)

They provide the exact split, so we can isolate “real” growth cleanly.

Q2 2025: License fees $7.010M, power pass-through $3.464M, total $10.560M

▼ ▼ ▼

Q3 2025: License fees $9.848M, power pass-through $3.553M, total $14.951M

What this tells you:

License fees jump hard (roughly +40% QoQ).

Power pass-through barely moves (roughly +3% QoQ).

So yes: you can track license fee growth as the true signal of HDC traction, and treat the power pass-through line as noise when you’re judging whether the pivot is working. That’s the mean to get there, not the ‘get there’.

License fee growth (so ignore the power pass-through noise)

As I said, Core’s colocation revenue is split into:

License fees (the real recurring economics, tied to contracted capacity)

Maintenance & other

Power fees (explicitly a pass-through dynamic, not the “value creation” line)

In Q3 2025, they disclose (in $ millions):

Total Colocation revenue: $14.951

License fees: $9.848

Power fees: $3.553

Same quarter Q3 2024:

Total Colocation revenue: $10.338

License fees: $7.806

Power fees: $2.487

So the clean read:

License fee growth (Q3 YoY): +26.2% (9.848 vs 7.806)

Power pass-through growth (Q3 YoY): +42.9%

License fees are ~66% of colocation revenue in Q3 2025 (the rest is mostly power pass-through and maintenance).

On the 9-month view (YTD through Sep 30):

License fees: $22.853m vs $11.625m (almost a doubling, +96.6%)

That’s exactly why we’re right to say: track license fees, not the electricity line. Power can balloon while value stays flat.

Customer concentration risk (CoreWeave dependence) (for now)

In the same Q3 2025 10-Q, Core discloses customer concentration by segment.

For Colocation, it shows 100% of revenue coming from a SINGLE CUSTOMER (they label it anonymously as a customer letter in the table, but it’s one customer, 100%).

Translation:

If that customer sneezes (delay, dispute, renegotiation, credit event), your “HDC transition” cash flow can face a cliff.

This is not a side risk. It is the risk until they diversify.

What makes it slightly less suicidal than it looks (still not “safe”):

These are long-term, capacity-style contracts. Our job is to confirm the take-or-pay, the remedies, the security package, and whether revenue recognition truly matches “ready-for-service” milestones.

(Long) Summary:

At the end of the day, the question is embarrassingly simple:

is Core Scientific actually turning “contracted megawatts” into “live megawatts that bill”?

Management’s story says the HDC ramp is roughly ~250 MW by end-2025 and ~590 MW by early-2027, that’s the backlog, the denominator. The problem is they don’t hand you a neat “MW ready-for-service” KPI in the Q3 2025 10-Q, so you have to infer progress from what they do disclose: license fees. Using their own headline economics (about $10B over ~12 years on ~590 MW, excluding power pass-through), you get a rough ~$1.41M per MW per year.

Plugging in reported HDC licensing revenue, it implies the MW that are actually live and billing likely moved from ~20 MW in Q2 2025 to ~32 MW in Q3 2025.

That’s progress, real directionally. And the quality of that progress looks decent because license fees (the real value line) jumped roughly +40% QoQ while power pass-through barely moved, meaning this isn’t just “electricity reimbursement inflating revenue,” it’s the contracted service revenue ramping. So yes, it’s going in the right direction, but with a giant asterisk: colocation revenue is still effectively single-customer (CoreWeave), so until they diversify, the entire HDC transition lives and dies on one throat to choke.

a 2024 snapshot.

So, the next logical question, what is the opportunity?

I made a conservative 10-year scenario, and the opportunity is simple: Core Scientific becomes a boring infrastructure landlord for high-density compute, with long contracts, predictable cashflows, and a business model that looks closer to “industrial real estate + power operations” than “crypto miner”. The prize is not “AI hype”. The prize is monetizing scarce (through high density), deliverable megawatts.

The opportunity

They sit on the bottleneck. Not GPUs. Power that is already packaged into sites you can actually run. If they keep executing, HDC turns their facilities into a leased vault for any workload that needs dense racks, uptime, physical security, and round-the-clock ops. AI/HPC is the wedge. Over time, the customer set can broaden into regulated industries and mission-critical operators that simply need compute capacity without building it themselves.

The logic is already visible in their own messaging: a multi-year ramp to hundreds of MW of HDC capacity (they’ve guided to a path like ~250 MW by end-2025 and ~590 MW by early-2027), plus “over $10B” of contracted revenue over ~12 years tied to that buildout (excluding power pass-through).

Where they could be in 10 years (conservative)

Again, a conservative thesis as the situation isn’t like a Google.

So again, in 10 years, so 2035.

Assume they keep doing what they’re doing currently, so without miracles:

HDC becomes the core, mining becomes a smaller, opportunistic sidecar. You see the direction already: HDC revenue rising while hosted mining is intentionally shrinking.

They deliver the contracted MW, then keep adding incremental capacity in smaller batches. Not “10 new mega sites”. More like steady expansions, one site at a time, funded sensibly.

Revenue quality improves: more comes from licensing fees (the real value line), less from pass-through electricity. In the near term you can already watch license fees growing much faster than power pass-through.

Customer concentration normalizes: today, colocation is effectively anchored by one customer (CoreWeave). In ten years, a conservative “success” looks like a handful of big customers, not one throat to choke…

If they simply execute the current contracted build, and then add modest expansion, a conservative destination is: a mid-size, high-density colocation platform with several hundred MW live and billing, producing a stable stream of license fees that the market starts valuing on contracted cashflow logic rather than on BTC cycles.

My honest “keep delivering like that” answer

Again,

Yes, it’s going in the right direction, and the opportunity is real. The company is trying to trade a volatile commodity business for an infrastructure business. If they keep delivering, the end state is predictable: less narrative risk, more execution risk, and a valuation framework that stops living and dying with the Bitcoin cycle.

One caveat you can’t dodge: the whole thing is currently extremely dependent on CoreWeave (commercially, operationally, and in funding dynamics). That is the single biggest reason a conservative scenario stays conservative until diversification is proven quarter after quarter.

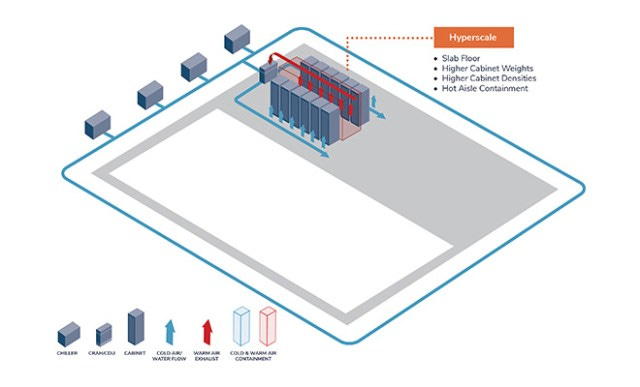

A short story about Cooling: Cooling tech and the density ceiling (where AI data centers quietly break)

Core Scientific’s pitch is very clear: “single-tenant”, “five-9s availability”, and 50–200+ kW per cabinet with advanced direct liquid cooling, delivered in big blocks (they explicitly talk about solutions “starting at 30 MW”).

That range matters because it basically telegraphs the cooling architecture they need to run: you don’t hold the upper end of those densities in production with “better fans”. You end up in hybrids (air + liquid) or DLC (direct-to-chip cold plates + CDU + facility water loop), with tight control on flow, pressure, filtration, materials compatibility, and dew point.

Now the investor problem: Core does not publicly give a clean KPI for “sustained production density achieved” by site (think: typical kW/cabinet under contract, at high utilization, over months). So you have to treat “50–200+” as capability marketing until you see proof through execution. Practically, that proof looks like: their MW go “ready-for-service”….again…, the license fees keep ramping, and customers keep expanding scope. The filings make clear the model: customers pay a base license fee tied to electric capacity plus power fees passed through without markup. That structure only works at scale if cooling stays stable under load.

Where these builds break is boring and mechanical, which is exactly why it’s deadly. Liquid loops introduce direct coupling between IT and facility cooling, so you inherit a new class of failure modes: corrosion from incompatible wetted materials (debris clogging cold plates), leaks at joints/couplings, pressure-drop issues starving part of the loop, condensation risk when control logic or setpoints drift, plus pump/CDU faults that turn into throttling events or service windows.

ASHRAE gets very explicit on coupling failure modes (pressure spikes, disconnection under flow/pressure, contamination, seal wear, water hammer). OCP bluntly says liquid cooling failures can be “more severe or even catastrophic” than air failures, and that serviceability and leak detection become first-order design constraints.

My take: Core’s upside in HDC comes from living comfortably in the “DLC/hybrid” world at scale, repeatedly, without turning ops into a maintenance circus. If they pull that off, they earn the right to monetize higher densities than a lot of generic colo, and the MW-to-billing ramp becomes credible. If they stall below the true high-density ceiling in production, they still have a business, but the differentiation compresses and competition tightens fast…

Competitive map: why Core Scientific, versus the ‘real’ specialists

If you want to judge Core Scientific properly, you can’t compare them to “data centers” in general. You have to map them against three archetypes, because each archetype wins for different reasons and sells a different flavor of “vault”.

Interconnect-heavy incumbents (Equinix-like)

These players win when the customer’s bottleneck is not power, but ecosystem. Dense carrier options. Cross-connects. Network gravity. Compliance comfort. A procurement team can sign them without explaining themselves for six months.

Core Scientific is weaker here. They don’t compete on being the world’s most connected campus. They compete on industrial delivery of dense power blocks. So if your workload is latency-sensitive and interconnect-heavy (finance, marketplaces, anything with lots of counterparties), the Equinix-style model is the default.

Where Core can still win: when the customer says, “I don’t need a network bazaar, I need a lot of MW, fast, and I’ll bring my own network design.”

Hyperscale build-to-suit (the “I’ll just build it” crowd)

This is the ruthless category. Big players with massive demand can finance their own builds or contract a developer to deliver custom campuses. They win on cost per MW at scale, on control, and on long time horizons. The trade-off is time, complexity, and permitting.

Core Scientific’s edge here is speed-to-MW using existing power sites. They’re basically selling a shortcut: repurpose and deliver faster than a greenfield project. The price is that the customer often pays a premium for time, and accepts less “perfect” customization than a fully bespoke build.

So Core wins when time matters and the customer is willing to pay for a faster ramp. Core loses when the customer can wait and wants ultimate control and lowest long-run cost.

The new “AI factories” (high-density, power-first, execution-first)

This is the emerging specialist layer. Everyone is trying to package the same thing: high-density racks, serious cooling, fast commissioning, and large MW blocks. The differentiator is not the brochure. It’s who can actually deliver under load, repeatedly, and scale from tens of MW to hundreds without slipping.

Core Scientific fits here by construction. They’re not coming from enterprise interconnect. They’re coming from the “ugly physics” side: power operations, always-on sites, and industrial uptime. Their pitch is basically: we already live in the world where heat and electricity are the boss.

The catch is that this category is the most brutally competitive on economics. The “AI factory” race tends to compress pricing once enough supply shows up. If Core wants to win long-term, they need either superior delivery speed, superior density capability, or superior cost of power. Preferably two.

The central question: where exactly does Core win, and at what price?

Core Scientific wins in one lane: large, high-density blocks of commissioned power delivered quickly, with an industrial single-tenant mindset. They are not the best interconnect hub. They are not the cheapest long-horizon builder. They are the “get me MW now, at high density, with a team that can run the vault 24/7” provider.

The price of winning that lane is clear:

You accept less ecosystem than the interconnect kings.

You accept higher execution risk than the mature incumbents, because delivery is the product.

And today, you accept higher customer concentration, because the model has been anchored by one major buyer.

So the bet isn’t “Core is the best data center company.” The bet is narrower: there will be a long period where speed-to-high-density MW is scarce, and Core can monetize that scarcity before the market commoditizes it.

Okay okay that’s cool mapping. But is there even an opportunity, I mean, why a company would choose CORZW 0.00%↑? And not the others I just cited.

We are saying the same thing again, but to be clear:

Why pick Core Scientific (strengths)

I. Speed to megawatts

High-density AI/HPC buyers care about one thing first: how fast can you hand me live, commissioned MW. Core Scientific starts with existing power sites and operations, then repurposes them. That can beat the multi-year greenfield cycle.

II. High-density DNA

They’ve been running power-hungry, always-on infrastructure for years (mining). Different workload, same brutal constraints: uptime, cooling, electrical discipline, on-site ops. HDC is basically that muscle pointed at GPU racks.

III. Single-tenant, industrial mindset

A lot of large AI customers want “my block, my rules, my ramp” rather than shared retail colocation. Core Scientific markets large blocks and phased delivery. That fits customers trying to scale to hundreds of MW.

IV. Potentially attractive economics for the buyer

If the operator can structure contracts where power is pass-through and the buildout is partially customer-funded, the buyer gets clarity on operating costs and timelines. Buyers like clarity. Especially at this scale.

V. Operational simplicity

For a customer, outsourcing the facility layer (power, cooling, physical security, 24/7 hands) reduces coordination. They keep the compute stack. Core runs the “vault”.

Why a customer might avoid them (weaknesses)

I. Less interconnection ecosystem than the classic hubs

Equinix-style campuses win on networks, cross-connect density, and ecosystem gravity. Core Scientific competes on power blocks and delivery. If your workload needs rich interconnect, carrier diversity, and proximity to a dense financial/network ecosystem, they may not be the first call.

II. Execution risk is the whole game

This business is construction, commissioning, and reliability under load. Delays hurt. Design mistakes hurt more. High-density cooling and power distribution punish sloppy work.

III. “Crypto miner” stigma (real, even if unfair)

Some enterprises and governments have procurement bias. They associate mining with volatility, reputational risk, and regulatory noise. That can slow deals, even if the HDC product is solid.

The trivial decision rule

Choose Core Scientific when you want big MW blocks, high density, fast delivery, and straightforward facility ops.

Choose a more traditional colocation/interconnection leader when you want ecosystem, networks, and a long history of enterprise procurement comfort.

My super honest take on the sector:

My take is simple: we’re going to see a first wave where the most “traditional” data-center players win a big share of the RFPs, mainly because procurement loves brand safety, compliance checklists, and vendor history. It’s the default path. But that’s not the end state.

As AI workloads mature, the use cases will fragment and specialize, and the compute race won’t be over, it will just get more demanding. The bottleneck will shift from “can you host servers?” to “can you host this kind of server, at this density, with this cooling, at this uptime, and deliver MW fast?” That’s when high-density operators and optimization-driven platforms start to matter.

Core Scientific is exactly that kind of bet: less about the polished enterprise ecosystem, more about industrial execution, high-density capacity, and the ugly physics of power and heat. That’s my dice roll.

Can they execute?

Management: do they actually have the people to pull off the pivot?

This transition does not fail because “AI demand disappears”. It fails because building and operating high-density sites at scale is a different sport than running a mining fleet. Different reflexes. Different procedures. Different tolerance for sloppiness. You can sell MW on a slide. You earn the right to bill MW by commissioning on time, holding temperature, hitting uptime, and keeping maintenance from turning into a circus.

Core’s most credible signal so far is simple: they staffed up like a real data center operator.

In their materials, they highlight a data center team with 150+ years of combined experience, with leadership pulled from the “grown-up” side of the industry (think Equinix, plus build / development backgrounds like QTS and big construction operators). That matters because it points to the three jobs that decide the outcome:

Operations discipline (COO / Data Center Ops).

If you come from an Equinix-type world, you’re trained to obsess over process, incident response, preventive maintenance, vendor management, and “boring reliability”. In high-density, boring wins. Every week.

Site development and delivery.

Head of Site Development plus a bench of site-development VPs is the right shape for a company whose product is literally “commission MW fast”. Permitting, procurement, construction sequencing, commissioning playbooks, change orders, contractor control. That’s where timelines slip and budgets blow up.

Scaling the org.

One “star operator” is useless. You need a repeatable machine: standards, staffing, spare parts, training, escalation paths, and a culture that doesn’t improvise at 3 a.m. with a customer screaming.

What I like (and why it’s a real positive)

Core is clearly trying to buy credibility with operator DNA. You don’t hire that profile if you plan to remain a miner with a side hustle. You hire it when you’re serious about becoming a power-and-cooling landlord with SLAs and enterprise-grade expectations.

Also, the team composition (ops + development + a layer of VPs) suggests they’re aiming for repeatability, not one-off hero projects. That’s exactly what the market will reward if the ramp shows up in the numbers.

What I don’t “give them for free”

A slide about resumes is still a slide.

The only proof that matters is operational output, quarter after quarter:

MW ready-for-service that actually grows (and ideally becomes a disclosed KPI).

License fees scaling faster than power pass-through (value creation, not just reimbursement).

Capex per MW staying sane (or clearly offset by customer funding).

Reliability under density: fewer “events”, fewer forced maintenance windows, no creeping opex explosion.

Customer diversification, because one anchor client makes your whole thesis fragile, regardless of how good your team is.

Valuation framework: how to pay for this thing now

Core Scientific sits in an awkward valuation gap. Part of the market still sees a miner with a volatile P&L. Which, don’t get me wrong, is the case for now. The HDC story wants a different lens: contracted infrastructure cashflows.

Our job as investors is to value it like a transition, not like a pure play.

The clean way to value HDC

I’d use two simple anchors, then triangulate.

A) EV / HDC license-fee run-rate

Ignore power pass-through. Treat it like a reimbursement line. The “real product” is the recurring license fee stream.

So you take annualized license fees (plus any recurring “maintenance/other” that behaves like service revenue), and apply an infrastructure multiple. Like I started to do.

B) EV / HDC EBITDA

Same logic, one level deeper. You estimate HDC gross margin and EBITDA margin on the license component, then compare to infrastructure peers. Not to miners. Not to “AI narratives”. To businesses whose cashflows are contracted and durable.

A simple reality check helps: if HDC becomes the dominant profit engine, you stop paying for BTC optionality. You pay for delivered MW that bill.

Valuation on the Conservative scenario (more short term)

I want to look 2 years in the future because that’s what we need to see if the transition is in the making: 8 Quarters.

That' will give me the confidence to back up the scenario above, the 2035, yet conservative, scenario.

By 2027 (not our former 2035), management talks about roughly ~590 MW in the contracted path. Conservative does not mean “they hit the slide”. Conservative means: they deliver a meaningful chunk, with some slippage, and billing ramps gradually.

Here’s a conservative, investable structure:

MW billing in 2027: 250–350 MW (not 590).

License revenue per MW per year: use the rough contract economics we backed into, around $1.4M/MW/year for hosting/licensing excluding power.

License run-rate in 2027:

250 MW → ~$350M/year

350 MW → ~$490M/year

Now margins. For HDC, the power passes through, so the cost structure revolves around operations, maintenance, staffing, security, and reliability capex. A conservative take assumes:

HDC EBITDA margin on license revenue: 35–55% (wide range, because execution quality decides it).

That yields HDC EBITDA in 2027:

250 MW case: ~$120–190M

350 MW case: ~$170–270M

Capex and free cash flow:

Capex per MW delivered sets the pain. If build cost per MW stays high, FCF stays muted even with strong EBITDA. If customer funding offsets a big chunk, the equity story improves fast.

Conservative FCF in 2027 looks like “positive but still reinvesting” rather than a dividend machine. I don’t want to see a dividend machine. I wnat to see a company that re invest. I want to see new plants; maybe acquire?The rerating often begins before peak FCF, once the delivery machine proves itself.

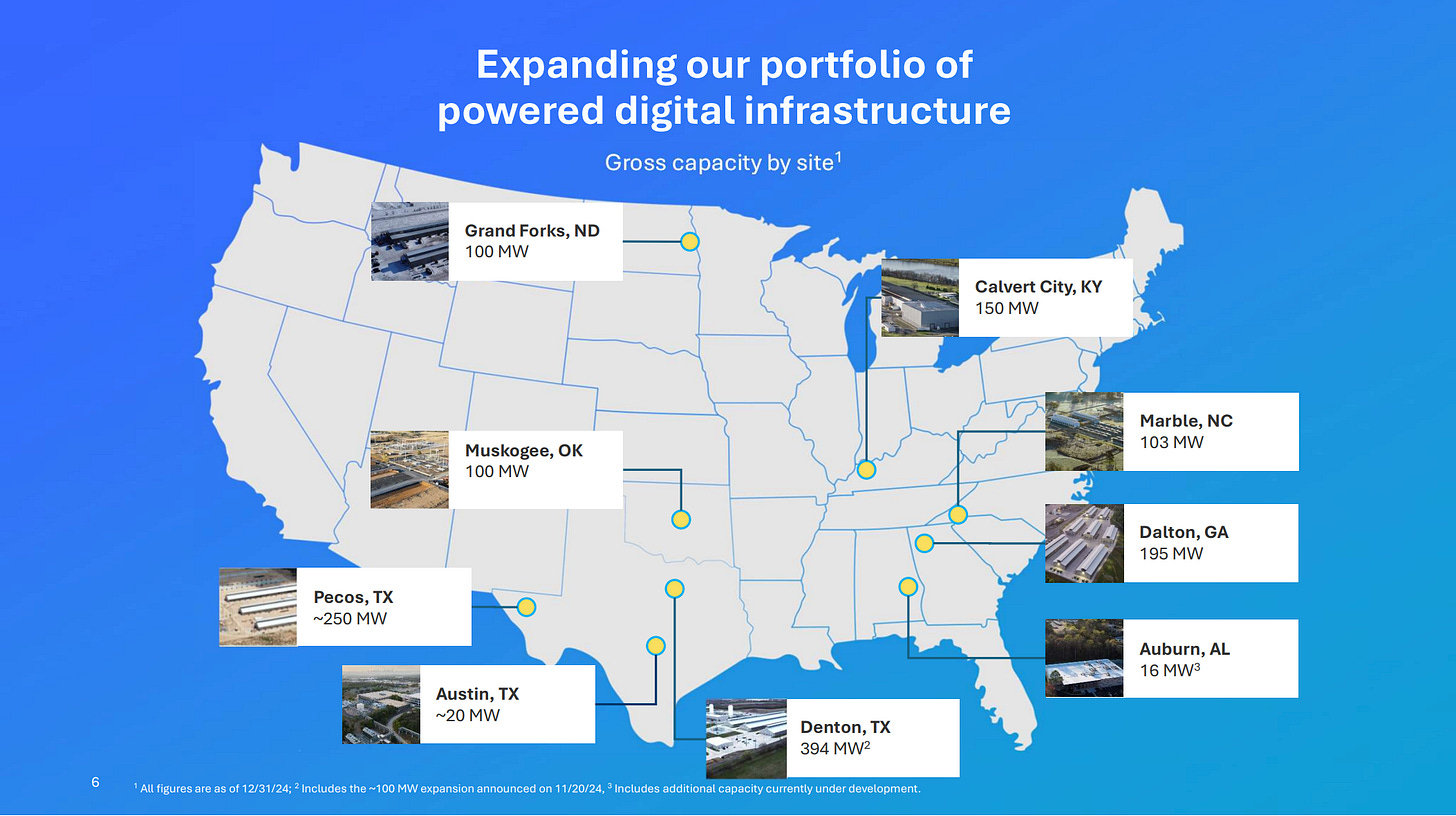

New plant? Here are the exiting ones;

▼ ▼ ▼

This is the heart of the bet: we’re paying today for a future where the market values a contracted license stream, even if near-term cash is still going into build-outs.

What would drive a rerate

A rerate happens when the story becomes boring or/and critically essential.

Delivered MW becomes a disclosed KPI and climbs steadily.

License fees keep scaling faster than pass-through power.

Customer concentration falls (two or three meaningful clients show up, not just one).

Funding risk drops (capex plan feels financed without constant dilution fear).

Mining becomes a sidecar whose swings stop dominating the narrative and the earnings print.

When those boxes tick, the market starts paying an “infra multiple” on the HDC stream, and the miner label fades.

What would drive a derate

Derate is brutal and predictable.

Delivery slips quarter after quarter, with vague explanations.

License fees stall while pass-through keeps growing (you’re selling electricity reimbursement, not a vault).

Core customer renegotiates, delays, or hits trouble. Concentration cuts both ways.

Capex explodes per MW, or funding tightens and dilution becomes the default.

Cooling and uptime issues show up in the form of penalties, service interruptions, or rising opex.

In short: the market derates when physics and financing win… Which can happen if we are honest.

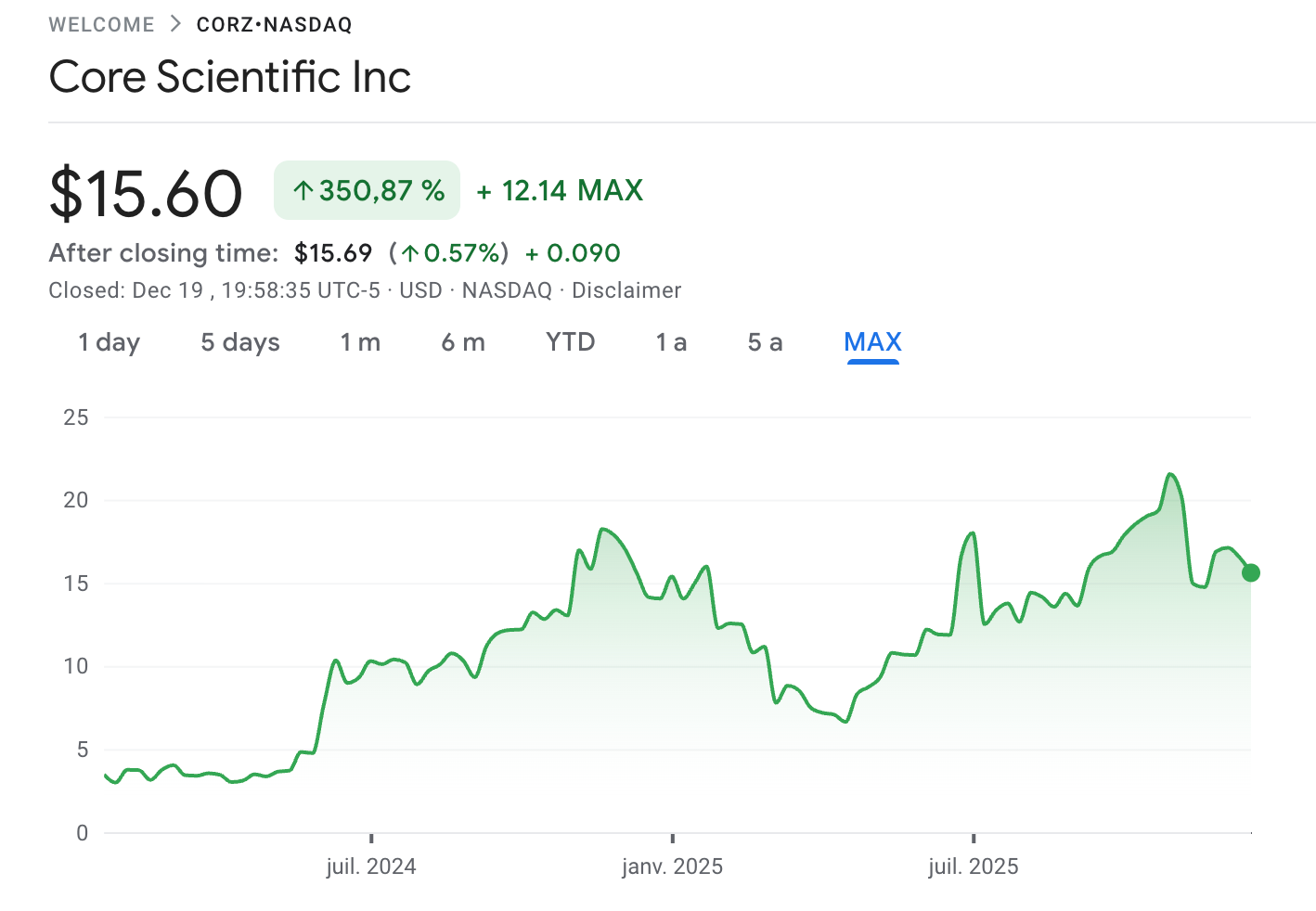

At $15, you’re not buying a “cheap miner.” You’re buying a transition into infrastructure, and a meaningful part of that future is already baked into the price.

What you’re actually buying when the market open…

Megawatts turning into leases, not bitcoins!

The core value driver is the shift from volatile mining cashflows to recurring HDC license fees (the real value line). Electricity is mostly pass-through noise. As long as license fees keep scaling, the pivot is alive. If license fees stall, the story slides back toward “miner with a data-center side project.”A 2026–2027 delivery ramp.

The market is pricing the expectation that Core keeps converting “contracted MW” into “MW that actually bill,” and that the pace accelerates.► This is an industrial execution bet, not a narrative bet.

A real dependency on an anchor customer (CoreWeave).

Right now, the HDC engine is essentially anchored by one customer. That helps speed, funding, and visibility. It also creates the main fragility: a delay, a renegotiation, or a dispute can hit the thesis immediately.An option on an “infrastructure rerating.”

If HDC becomes the dominant profit engine, the market can start valuing Core more like a contracted infrastructure business and less like a BTC cycle proxy. That’s the clean upside.

…and what to expect if you pay $15

Volatility. Each quarter will feel like a referendum on execution (license fee growth, delivery progress, capex discipline, uptime, timelines).

Ugly margins early. Ramps are expensive. The key is whether margins improve with scale. If they don’t, something is wrong operationally.

Crypto headlines will still bleed into the stock. As long as self-mining remains a large part of the revenue mix, BTC sentiment will keep contaminating perception.

A semi-binary outcome profile. Not literally all-or-nothing, but clearly asymmetric: if HDC execution is clean, it becomes a durable rent-like stream; if it slips, you’re left holding a capital-intensive build with concentration risk and a mining segment that doesn’t really “protect” you.

The valuation reality in one sentence

At $15, you’re already paying for hundreds of MW of HDC billing power by 2027 even though today’s reported HDC results still reflect the early innings. So you’re not getting a balance-sheet margin of safety.

Your margin of safety is execution.

Conclusion (what this is really about, and what you should do)

This piece is a plumbing thesis.

The point is that the “vault” has moved. Value is increasingly stored, recorded, and transferred inside digital registries, and those registries depend on something brutally physical: power, cooling, uptime, access control, operators.

So the weight, the length, the security of the vault is now the density of the data center.

The data center stops being “IT” and starts behaving like a shared institutional layer. A vault you rent. A vault you scale. A vault you trust because it stays up.

That’s why High-Density Colocation (HDC) matters. It’s the industrial answer to a simple constraint: modern workloads (AI/HPC, but also anything mission-critical) are turning electricity into value, and they need facilities that can handle extreme density without breaking.

Core Scientific is interesting because it sits right on that seam. It used to monetize megawatts by mining Bitcoin. Now it’s trying to monetize megawatts by leasing them as “vault capacity” to high-density customers. The upside is clean: if they execute, the company gradually stops being priced like a miner and starts being priced like contracted infrastructure. The risk is also clean: the transition is still early, heavily dependent on one anchor customer, and the real bottleneck is execution under load (delivery, cooling, reliability).

So what should you do as an investor?

If you want a “stable infrastructure compounder” today, this is not it yet. You wait. You let the ramp prove itself.

If you’re willing to pay $15 for a transition, then your job becomes narrow and mechanical: watch whether license fees keep compounding (real value line), whether “MW contracted” actually turns into “MW billing,” and whether customer concentration starts to loosen. If those three move the right way, you hold and add. If they don’t, you don’t rationalize. You leave!

At $15, you’re not buying a finished vault. You’re buying the construction site, plus the right for it to become a rent-producing vault. If the build stays on schedule, this can evolve into real infrastructure, and you’ll get paid for owning that. You buy also the bet on: high-density operators and optimization-driven platforms start to matter.

Also, I’m betting on the fact that this high-density vault layer will end up serving critical industries that don’t have the luxury of downtime, procurement experiments, or half-baked infrastructure. Finance, healthcare, government workloads, industrial simulation, even parts of energy and manufacturing. Different use cases, same primitive: a registry and the compute that keeps it alive. As those sectors digitize deeper, they’ll need places where high-power racks can run with predictable uptime, controlled access, and operational discipline, without every institution having to become its own mini-hyperscaler. If Core can keep proving it can deliver dense, reliable MW at scale, the customer base doesn’t have to stay “AI-native forever.” It can broaden into the parts of the economy where failure is not a PR problem, it’s a systemic event. That’s the longer-duration bet behind the bet.

If physics, delays, or concentration risk win, it stays a volatile story wearing an infrastructure costume. But at 15$/ share, buying 10 shares, just to see “how it goes” you don’t take much risks…

What is kW per Rack?

Kilowatt per rack (kW/rack) is the power assigned to a server rack in a data center. It is measured in kilowatts (kW) and represents the total power needed for all IT equipment in that rack. Colocation providers offer different power levels:

Low-Density: 2–5 kW/rack

Mid-Density: 6–9 kW/rack

High-Density: 10–50 kW/rack

Power density depends on server type, workload, and cooling efficiency. Colocation providers set power limits based on their electrical and cooling capacity. Higher-density racks allow businesses to use fewer racks, reducing costs and space.

Data centers also track Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) to measure energy efficiency. A lower PUE means better efficiency. The best data centers aim for a PUE of 1.2 or lower.

Why Power Density Matters

Power density affects efficiency, costs, and scalability. Higher power density means data centers can support stronger workloads in less space. Businesses using AI, machine learning, or high-performance computing (HPC) often need higher kW/rack values.

Understanding power density helps businesses avoid wasted space or overusing energy. As edge computing and IoTgrow, companies need better power distribution strategies. High-density racks help deliver low-latency services where space is limited.

More industries are using cloud-based solutions, increasing the demand for high-density colocation. Businesses using hybrid cloud models must consider kW/rack when choosing a colocation provider.

Data centers are also using AI-powered energy management to improve efficiency and reduce energy waste. These innovations make colocation a cost-effective and sustainable solution.

How High-Density Workloads Affect Power Use

New technologies like AI, machine learning, and big data increase power use per rack. This leads to:

Higher Cooling Needs: More power generates more heat, requiring better cooling, such as liquid cooling.

Higher Energy Costs: More power means higher colocation bills.

Better Space Use: High-density racks reduce the number of racks needed.

Infrastructure Upgrades: Some data centers need new electrical and cooling systems to support high-density setups.

From Datacenter.com